Situation analysis

Introduction

Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is context-specific, with many approaches potentially being CSA somewhere, but no single practice being CSA everywhere. What is climate-smart also changes with time. This means that when initiating new activities, restructuring existing agricultural programs to enhance CSA goals, or scaling up ongoing projects, CSA interventions should be designed with a thorough understanding of the contextual reality a program will be implemented within.

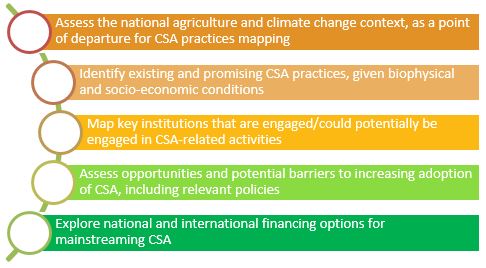

The first step in establishing a CSA program is to conduct a situation analysis, capturing the current status of CSA initiatives, vulnerabilities and threats given specific contexts, as well as the enabling environment across sectors and at multiple levels. The agricultural, political, social, environmental and economic contexts in which the CSA approach is being applied should be explored, highlighting the entry points for investing in priority CSA initiatives at scale. Content of the situation analysis is usually based on existing global and national data sources, as well as expert input and surveys ideally including farmers and technical experts, and can also incorporate more localized data if available.

Situation analysis can cover a range of topics, but generally involves the following type of information:

An example of the result of a situation analysis is the CIAT and CCAFS developed CSA Profiles, the contents of which are described below.

Case study

Tools

References

-

1

FAO. 2013a. Climate-Smart Agriculture: Sourcebook. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3325e.pdf Between now and 2050, the world’s population will increase by one-third. Most of these additional 2 billion people will live in developing countries. At the same time, more people will be living in cities. If current income and consumption growth trends continue, FAO estimates that agricultural production will have to increase by 60 percent by 2050 to satisfy the expected demands for food and feed. Agriculture must therefore transform itself if it is to feed a growing global population and provide the basis for economic growth and poverty reduction. Climate change will make this task more difficult under a business-as-usual scenario, due to adverse impacts on agriculture, requiring spiralling adaptation and related costs. -

2

Hill Clarvis M. 2014. Review of Financing Institutions and Mechanisms, in Financing Strategies for Integrated Landscape Investment. Washington, DC: EcoAgriculture Partners, on behalf of the Landscapes for People, Food and Nature Initiative.

http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/ffd3/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/10/ReviewofFinancingInstitutionsandMechanisms_HillClarvis_April2014.pdf Integrated landscape management (ILM) approaches are key to addressing the interdependent resource governance and management challenges that a range of stakeholders face (small holders and farmers, agribusiness, local communities, utility operators, regional and local governments) within a given landscape. ILM refers to long-term collaboration among different groups of land managers and stakeholders to achieve the multiple objectives required from the landscape, reducing tradeoffs and strengthening synergies among the different landscape objectives. There is concern that there are major barriers to sources of funding and finance for such ILM initiatives due to the misalignment between such multi-benefit and multi-actor approaches and the siloed financial mechanisms for specific sectors or policy goals (e.g. agriculture, renewable energy, food security, climate adaptation, climate mitigation, catchment management). The report tracks innovations in ILM finance across the public and private sector. -

3

DFID.1999. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. Lodnon, United Kingdom: Department for International Development (DFID).

http://www.livelihoodscentre.org/-/sustainable-livelihoods-guidance-sheets?inheritRedirect=true The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) concept and framework adopted by DFID in the late 1990s (building on work by IDS, IISD, Oxfam and others) have been adapted by different organisations to suit a variety of contexts, issues, priorities and applications. Core to livelihoods approaches are a set of principles that underpin best practice in any development intervention: people-centred, responsive and participatory, multi-level, conducted in partnership, sustainable and dynamic. -

4

Elasha BO, Elhassan NG, Ahmed H, Zakieldin S. 2005. Sustainable livelihood approach for assessing community resilience to climate change: case studies from Sudan. Assessment of impacts and adaptations to climate change (AIACC) Working Paper No. 17. AIACC.

http://www.start.org/Projects/AIACC_Project/working_papers/Working%20Papers/AIACC_WP_No017.pdfExposure to climate variability and extremes, most particularly drought, poses substantial risks to people living in the Sudano-Sahel region. In several rural communities of Sudan, community based sustainable livelihood (SL) and environmental management (EM) measures have been implemented to build resilience to the stresses of drought and other climate variations and extremes. It is hypothesized that these measures also build resilience and adaptive capacity that lessen the vulnerability of rural communities of the region to future climate change. A research method based upon a sustainable livelihood conceptual framework is being developed and applied in case studies in Sudan to evaluate the performance of sustainable livelihood and environmental management measures for building resilience to today’s climate-related shocks and for their potential for reducing community vulnerability to future climate change. The initial design of the sustainable livelihood framework and research method are described in this paper. As research on the case studies progressed, the framework and method were modified in response to the specific contexts of the selected cases. The revised framework and method will be described in papers on the case studies that are in preparation. Sustainable livelihood assessment is intended to generate an understanding of the role and impact of a project on enhancing and securing local people’s livelihoods. As such, it relies on a range of data collection methods, a combination of qualitative and quantitative indicators and, to varying degrees, application of a sustainable livelihoods model or framework. The research used the sustainable livelihood model of UK Department of Foreign and International Development (DFID), and the notion of the five capitals (natural, physical, human, social and financial), albeit loosely, in order to frame the inquiry and capture perceptions of coping/adaptive capacity in the data collection process. Primary results obtained so far indicate that the framework can be a useful tool in understanding the impact of sustainable livelihood measures in increasing communities' resilience to climatic stresses - mainly drought - from local people’s point of views.

-

5

GIZ. 2014. Framework for Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment.

https://www.weadapt.org/sites/weadapt.org/files/legacy-new/knowledge-base/files/5476022698f9agiz2014-1733en-framework-climate-change.pdfThis framework was prepared to provide decisionmakers and adaptation implementers such as (local) government officials, development experts and civil society representatives with a structured approach and a sourcebook for assessing vulnerability to climate change. Furthermore, it provides a selection of methods and tools to assess the different components that contribute to a system’s vulnerability to climate change. Key questions to be addressed are: • How to plan for a vulnerability assessment? • Which tools or methods to select to carry out a vulnerability assessment? • How to carry out a vulnerability assessment? The reader will first be acquainted with the theoretical background behind the concept of vulnerability. Next, two broad approaches for assessing vulnerability will be introduced: Vulnerability assessments can be carried out either at a local level using participatory methods and tools as well local climate data (bottom-up assessments) or at state, national or global level using large-scale simulation models and statistical methods (top-down assessments). The introduction to the concept of vulnerability is followed by the main framework consisting of four different stages for assessing a system’s vulnerability to climate change. Each stage in the vulnerability assessment consists of steps that specify which kinds of analyses should be carried out in that stage. Every step contains a set of guiding questions and a list of suggested methods and tools that can be used to answer these questions. Each stage of the framework is followed by two practical examples of vulnerability assessments carried out in India: A bottom-up vulnerability assessment carried out at the outset of a GIZ supported climate change adaptation project and a top-down vulnerability assessment carried out for the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh as a whole. Finally, the reader is presented with an extensive yet not exhaustive selection of methods and tools that can be used to assess the components of vulnerability to climate change at different levels.

-

6

World Bank. 2011. Weather index insurance for agriculture: Guidance for development practitioners. Agriculture and Rural Development Discussion Paper 50.

http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2012/01/19/000356161_20120119000449/Rendered/PDF/662740NWP0Box30or0Ag020110final0web.pdf Since the late 1990s, there has been a lot of discussion and debate about the promise and potential uses of index based agriculture insurance. The following paper is a distillation of the findings of the work undertaken by the World Bank. It is deliberately not a collation of case studies, but rather a practical overview of the subject. The purpose of this paper is to introduce task managers and development professionals, who are not insurance sector specialists, to weather index insurance. We seek to place this relatively new insurance product in a broader context of agricultural risk management and more specifically within the context of agricultural insurance. Ultimately, the paper seeks to take the reader through the main decision points that would lead to a decision to embark upon a weather index insurance pilot and then assists them to understand the technical procedures and requirements that are involved with it. In addition, the paper seeks to advise the reader of the practical challenges and implications that are involved with a pilot of this nature and what they might expect to encounter during the initial stages of implementation.