Monitoring, evaluation and learning

Introduction

CSA plan’s monitoring, evaluation, and learning (ME&L) component develops strategies and tools to track progress of implementation, evaluate impact, as well as facilitate iterative learning to improve CSA planning and implementation. CSA Plan’s ME&L delivers processes and products to support achieving and documenting program goals and adaptively managing implementation. The primary audience of the ME&L component of CSA Plan is program and project designers and managers.

CSA aggregates outcomes from individual efforts towards the common set of goals of a more productive, resilient and lower emission food system. While the scale and scope of activities certainly differ, they may all contribute to CSA objectives. The fundamental premises underlying CSA Plan’s ME&L is that CSA is a gradient and not an endpoint and that CSA is context (place and time) specific. The triple win of productivity, resilience and mitigation may not be achievable or prioritized in all places. This means that the standards for performance and learning need to be specific to a societal aim and specific to a time and place. This precondition of clear objectives will typically be informed by step 1 in CSA Plan (‘situation analysis’) and set in Step 2 (‘targeting and prioritizing’).

Outcomes are measured using indicators and metrics where at least two key principles should be considered:

- There should be a minimal set of high-level indicators tracked across programs to allow easy measurement and facilitate comparability. Additional higher resolution and indicators that are more specific may be important for specific projects. It is important to note that there are many groups globally (e.g. World Bank and CCAFS, see cases) working to set this high-level set of indicators and initial release should be forthcoming in April 2016.

- Indicators should be ‘SMART’: simple, measurable, accurate, reliable and time bound, which allow tracking of performance and change in condition.

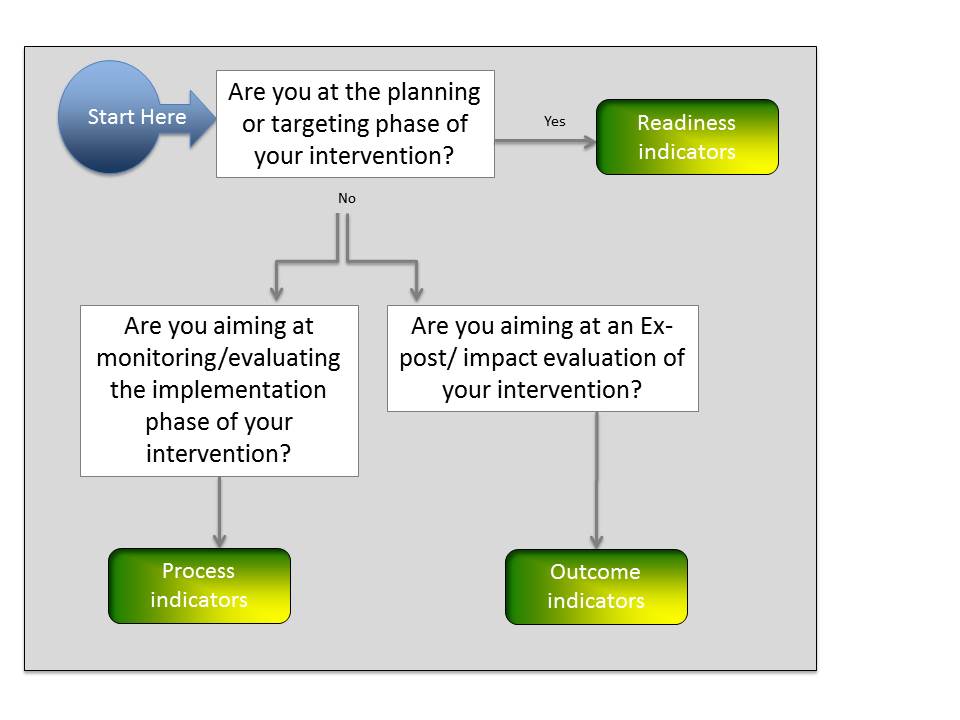

CSA plan ME&L approach uses a simple three-step process to help determine which type of metrics, indicators, and monitoring approaches are suitable for a given context. The decision tree in Fig. 1 helps to determine the categories of relevant CSA indicators. Oftentimes, implementation of CSA across the entire program lifecycle will require all three categories (or use-cases) of indicators that follow:

Figure 1. Simple decision tree to determine which use- case to select from. Typically, you will need to select and use indicators from each group throughout the project lifecycle. Each use case is described below. Based on an extensive database of indicators, CCAFS in the context of collaboration with USAID Feed the Future has developed a new tool to plan CSA projects and indicators (see the CSA Programming and Indicator Tool).

CSA Plan’s indicators use-cases for the project lifecycle:

- Readiness indicators

- Process indicators

- Progress/impact indicators

Readiness indicators: The first use case is to determine readiness for a CSA intervention. Readiness is important because CSA requires many supporting structures for success and sometimes the intervention necessitates preliminary capacity building to precondition the location or target population. Readiness indicators need to be tied to the type of intervention designed (See case study 3). For example, if a project desires to scale-up agroforestry in the Western Kenya, it will be important to know items such as the status of the extension system, network of nurseries, land tenure, etc. The information needed may be significantly different from that for an intervention designing an early warning system or insurance scheme.

Process indicators: CSA Plan advocates inclusive, transparent, and responsive processes to enable adaptive management, learning, and tracking of project implementation. Process-oriented indicators allow programs to be evaluated for meeting CSA and planned objectives. Certain ME&L indicators provide insights into implementation processes such as the diversity and gender of team composition, number and quality of interactions with communities, timeliness of reporting, etc. While often neglected in many development programs, CSA Plan proposes that the importance of these indicators cannot be understated as they provide purchase for just, equitable and transparent processes.

Progress/impact indicators: A key distinguishing feature of M&E for CSA is the need to understand the impact on all three objectives. One can use either input or outcome indicators to measure progress or impact. Input indicators typically rely on assumptions about the relationships between activities in an outcome. For example, adoption of conservation agriculture increases the resilience to intra-seasonal droughts. Or use of nitrogen fertilizer affects nitrous oxide emissions. While tractable, in many cases the relationships between inputs and outcomes are not well documented or are site specific. Thus, the magnitude of change is difficult or impossible to ascertain. Alternatively, one can measure direct indicators of outcomes of interest (see case studies 1 and 2). Numerous individual indicators can describe each pillar. For example, productivity may be illustrated by changes in yield, calories, or income (see Measuring productivity below). Or mitigation may be characterized by carbon sequestration or greenhouse gas emission per unit product (see Measuring mitigation below). Resilience indicators are more challenging, with both proxy and process indicators being commonly use (see Measuring adaptation and resilience below). The diversity of indicators with productivity and mitigation and the varying opinions and options of indicators for resilience further reinforce the need to select indicators will end users in a participatory process so that they reflect their goals (see toolboxes for further references).

Key resources

Gujit I, Woodhill J. 2002. Managing for impact in rural development. Rome, Italy: IFAD.

https://www.ifad.org/documents/10180/17b47fcb-bd1e-4a09-acb0-0c659e0e2def

This Guide has been written to help project managers and M&E staff improve the quality of M&E in IFAD-supported projects. The Guide focuses on how M&E can support project management and engage project stakeholders in understanding project progress, learning from achievements and problems, and agreeing on how to improve both strategy and operations.

The main functions of M&E are: ensuring improvement-oriented critical reflection, learning to maximise the impact of rural development projects, and showing this impact to be accountable. The Guide is meant to improve M&E in IFAD-supported projects, as a study found that most projects have a fairly low standard of M&E. The Guide provides comprehensive advice on how to set up and implement an M&E system, plus background ideas that underpin the suggestions.

World Bank. 2004. Monitoring and evaluation (M&E): Some tools, methods & approaches. Washington, DC: World Bank.

http://www.worldbank.org/oed/ecd/tools/

Government officials, development managers and civil society are increasingly aware of the value of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of development activities. M&E provides a better means of learning from past experience, improving service delivery, planning and allocating resources, and demonstrating results as part of accountability to key stakeholders. Yet there is often confusion about what M&E entails. This booklet therefore presents a sample of M&E tools, methods and approaches, including several data collection methods, analytical frameworks, and types of evaluation and review. For each of these, a summary is provided of the following: their purpose and use; advantages and disadvantages; costs, skills, and time required; and key references.

UNFCCC. 2010. Synthesis report on efforts undertaken to monitor and evaluate the implementation of adaptation projects, policies and programmes and the costs and effectiveness of completed projects, policies and programmes, and views on lessons learned, good practices, gaps and needs. Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice 32nd session. Bonn, 31 May to 9 June 2010. Bonn, Germany: UNFCCC.

http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/sbsta/eng/05.pdf

This document synthesizes information contained in submissions from Parties and organizations and in other relevant sources on efforts undertaken to monitor and evaluate the implementation of adaptation measures, including projects, policies and programmes. This document synthesizes efforts in this area and also reports on the development and use of adaptation indicators. A summary of lessons learned, good practices, gaps and needs is provided, and the document concludes by raising issues for further consideration.

Lamhauge N, Lanzi ER, Agrawala S. 2012. Monitoring and evaluation for adaptation: Lessons from development co-operation agencies. OECD Environment Working Paper No. 38. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

http:// dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg20mj6c2bw-en

In the context of scaled up funding for climate change adaptation, it is more important than ever to ensure the effectiveness, equity and efficiency of adaptation interventions. Robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is an essential part of this, both to ensure that the prospective benefits of interventions are being realised and to help improve the design of future interventions. This paper is the first empirical assessment of M&E frameworks used by development co-operation agencies for projects and programmes with adaptation-specific or adaptation-related components. It has analysed 106 project documents across six bilateral development agencies. Based on this, it identifies the characteristics of M&E for adaptation and shares lessons learned on the choice and use of indicators for adaptation.

Colomb V, Bernoux M, Bockel L, Chotte J-L, Martin S, Martin-Phipps C, Mousset J, Tinlot M, Touchemoulin O. 2012. Review of GHG calculators in agriculture and forestry sectors: A guideline for appropriate choice and use of landscape based tools. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ex_act/pdf/ADEME/Review_existingGHGtool_VF_UK4.pdf

Climate change and its consequences are now recognized amongst the major environmental challenges for this century. Land based activities, mainly agriculture and forestry, can be both sources and sinks of greenhouse gases (GHG). In most countries, they represent significant share of total GHG emissions, around 30 % at global level. In order to reach global or national reduction target, as well as meeting food security challenges, agriculture and forestry sectors need to evolve. In parallel to IPCC work and progress on methodological issues, many GHG tools have been developed recently to assess agriculture and forestry practices. Denef et al. (2012) classify these tools as : calculators, protocols, guidelines and models. This review focus on calculators, i.e, automated web-, excel-, or other software-based calculation tools, developed for quantifying GHG emissions or emission reductions from agricultural and forest activities. This review considers calculators working at landscape/farm scale, including several productions: crop, livestock and forest. Eighteen major calculators were identified, amongst them EX-ACT, ClimAgri, Cool Farm Tool, Holos, USAID FCC and ALU.

Approaches and tools

In this section, we will describe select approaches, tools and cases that guide and exemplify an entire process or to facilitate specific elements of the process.

CCAFS has created a database of over 378 CSA-related indicators gathered from several international development agencies (FAO, DFID, GIZ, IFAD-ASAP, World Bank, USAID) to develop a public access CSA Programming and Indicator Tool to contribute to address both, the need of good instruments for CSA programming and better metrics for tracking outcomes and impacts. The Tool proposes a shared framework for agricultural programs to: i) examine to what extent current or planned intervention(s) address each CSA pillar, ii) compare the scope and CSA intentionality among different project designs to make future programming more climate-smart, and iii) support the identification and selection of an appropriate set of indicators to measure and track CSA related outcomes.

Readiness indicators

Progress indicators

References

-

1

Wollenberg E, Zurek M, De Pinto A. 2015. Climate readiness indicators for agriculture. CCAFS Info Note. Copenhagen, Denmark: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/68685/CCAFS%20info%20note%20readiness%20indicators%20Oct%202015%20final%20A4%20%281%29.pdf?sequence=11&isAllowed=y Countries vary in their institutional technical and financial abilities to prepare for climate change in agriculture and to balance food security, adaptation, and mitigation goals.Indicators for climate readiness provide guidance to countries and enable monitoring progress. Readiness assessments can enable donors, investors and national decision-makers to identify where investments are needed or likely to be successful. Examples of climate readiness indicators are provided for five work areas: 1. governance and stakeholder engagement, 2. knowledge and information services, 3. climate-smart agricultural strategy and implementation frameworks, 4. national and subnational capabilities and 5. national information and accounting systems. -

2

IFAD. 2012a. Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme (“ASAP”) Programme Description. Rome, Italy: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

http://www.ifad.org/climate/asap/note.pdfASAP is a new direct entry point in IFAD to channel earmarked climate and environmental finance to smallholder farmers. ASAP funds will co-finance projects using clear selection criteria and applying a results framework which contains 10 specific and measurable indicators of achievement. An important element of ASAP will be a knowledge management programme that will develop and share climate adaptation lessons and tools across IFAD‘s programmes and with key external partners. Based on a thorough monitoring and evaluation system, this is expected to demonstrate the value of investing climate finance in smallholders to the Green Climate Fund and other climate initiatives. Investment areas are determined by the needs identified by partner communities.